Difference between katana and tachi

Katana (Uchigatana) VS Tachi

Those new to the world of Japanese swords may find themselves often confused about two swords: the katana and the Tachi. It's interesting to note that actually all Japanese swords are called 'Katana 刀', the type we often refer to is actually the Uchigatana 打刀. So, a more precise comparison would be between the Uchigatana and the Tachi 太刀.

Uchigatana and Tachi might seem similar, but they have their own unique qualities. In this article, we'll explore what sets each sword apart in a clear and engaging way. We'll look into how they were historically used, their distinctive features, and their significance in the rich tapestry of Japanese history.

Table of Content

- Distinguish Katana (Uchigatana) and Tachi by the way they wore and display

- Distinguish Katana (Uchigatana) and Tachi by the blade length

- Distinguish Katana (Uchigatana) and Tachi by the blade shape (姿)

- Distinguish Katana (Uchigatana) and Tachi by their Koshirae (Fittings)

- Katana and Tachi history

How to distinguish Katana (Uchigatana) and Tachi

Katana (Uchigatana) and Tachi, they are both long, curved Japanese swords, at first glance it's difficult to tell the difference, but don't worry, this article will break it down point by point:

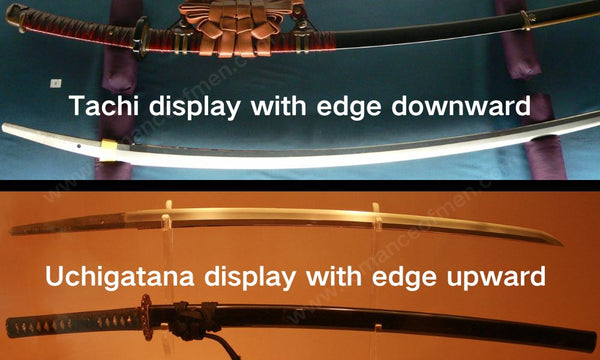

Distinguish Katana (Uchigatana) and Tachi by the way they wore and display

This is probably the most obvious way to distinguish Katana and Tachi, if the user really knows the correct way to wear or display it.

Tachi swords were traditionally worn hanging from the waist with the blade facing down, a style convenient for cavalry. Same for display, Tachi should be displayed with edge facing down, and tsuka (handle) facing left, sometimes Tachi was displayed horizontally to highlight their elegant curvature as well.

Uchigatana, in contrast, were worn thrust through the belt with the blade facing upwards, a practical choice for foot soldiers and samurai, and are typically displayed vertically also with blade facing upward, emphasizing their functional design.

Distinguish Katana (Uchigatana) and Tachi by the blade length

Although there are no strict regulation on the blade length for both Uchigatana and Tachi, and often times the blade length is customized to fit the wielder, Uchigatana and Tachi has obvious enough blade length difference.

Uchigatana blade length: Usually around 70cm (27 inches). In Japanese measurements, that's about 2 shaku 3 sun.

In ancient Japan, under the rule of Tokugawa Iemitsu (徳川家光), they limited the blade length of Uchigatana no longer than 70cm. Many katanas made before this period were longer, and were modified by shortening the tang (茎 nakago) to comply withe laws. This process is called 'Suriage' (磨上げ)

Tachi blade length: Usually about 75.8 to 78.8 cm (29.8 to 31 inches, or about 2 shaku 5 sun to 2 shaku 6 sun). There are even longer Tachi (Odachi 大太刀) with blade length over 90cm (35 inches).

We can see that, Tachi is usually a bit longer than Uchigatana. But blade length shouldn't be the only factor, because there is a smaller type of Tachi called Kodachi 小太刀, the blade length is only 60cm (23.6 inches), it's easy to confuse Kodachi with Uchigatana, or even wakizashi 脇差, if you try to distinguish them by blade length only.

Distinguish Katana (Uchigatana) and Tachi by the blade shape (姿)

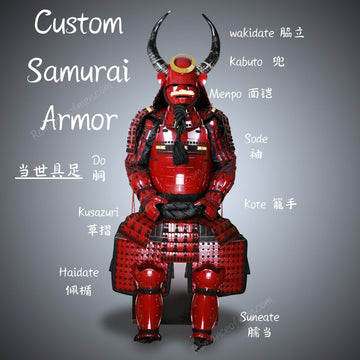

The "katana shape" (姿 'sugata') refers to the overall form and characteristics of a Japanese katana sword. It includes various elements that define the sword's appearance and structure. such as Curve (反り, 'Sori'), blade length (刃長 nagasa), Width (元幅, 'Motohaba'), thickness (元重ね, 'Motokasane') etc. We can use blade shape to distinguish Katana and Tachi.

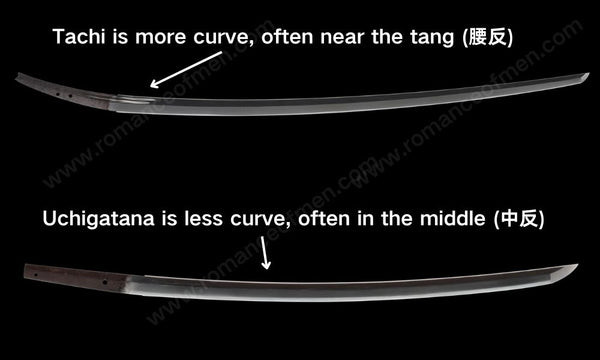

Curvature (Sori):

Tachi (太刀):

Generally features a deeper curvature.

The curvature is often centered near the handguard (腰反り, 'koshi-zori').

The deep curvature helps in the 'striking and pulling' motion during cutting, making it efficient for use on horseback, where Tachi was primarly used.

Uchigatana (打刀):

As Uchigatana became more popular, its design included a flatter construction (平造り, 'hirazukuri'), initially resembling longer versions of Tanto.

Later, it adopted a ridge-line style (鎬造り, 'shinogi-zukuri'), like Tachi, but with less pronounced curvature.

Blade Width (Motohaba):

Tachi:

Features a blade that narrows from the base (元幅, 'motohaba') to the tip (先幅, 'sakihaba'), adding to its elegance.

Known for its 'small tip' (小鋒/小切先, 'kogissaki') look.

Uchigatana:

Later designs adopted similar width characteristics as Tachi.

Distinguish Katana (Uchigatana) and Tachi by their Koshirae (Fittings)

The difference between Tachi Koshirae and Katana Koshirae lies in their historical use and design. Tachi Koshirae were originally crafted for ceremonial and mounted combat purposes, featuring a more elaborate decorations style. On the other hand, Katana Koshirae evolved for practical use in infantry warfare, with a focus on simplicity and functionality. The transition from Tachi to Katana reflects changes in combat styles, and each has its unique place in Japanese sword history.

Katana and Tachi history

The tachi came first during the late Heian period, known for its curved shape, suitable for mounted battles. The uchigatana, a bit shorter and less curve than Tachi, became popular in the late Muromachi period, worn by inserting into the obi for easy use. Despite the rise of uchigatana, commanders still favored the tachi, while foot soldiers adopted the more convenient uchigatana. The transition reflects changes in combat styles, with tachi worn during mounted battles and uchigatana becoming mainstream in infantry warfare. Large tachi (Odachi) from the Nanboku-cho period were often shortened and reused as uchigatana. The history of these swords is intertwined with the evolution of combat and changing preferences.