Katana Nakago The tang of the sword hides more secrets than you thought

Everything You Need To Know About Katana Tang - Nakago

Nakago is the tang of a Katana sword. Because it was not visible in most cases, people might not know the importance of nakago in a katana. This guide will discuss everything you need to know about Nakago, from history, shapes and types. You will understand better Nakago after you read this guide.

Table of Content

- What Is Nakago 茎?

- Functionality of Nakago

- Sword's Information from Nakago

- Nakago Parts

- Types of Nakago

- Nakago Shapes

What Is Nakago 茎?

The Nakago "茎" is the Tang of Katana. It is the Katana blade's extension into its handle. In Japanese, 茎 literally means stem. It makes sense and easy to understand, because in Japanese, the word Katana "刀" refers to the blade only, without any fitting like sheath (Saya) or hilt (tsuka). Nakago is the only part of a blade you can hold because it has no edge.

In Japanese, Nakago were also called 中心 (Chūshin), 忠 (Chū) or 柄心 (Eishin), but Nakago "茎" is the most common name.

Nakago is often overlooked because it was hide underneath the tsuka. It actual plays a vital role in katana's balance and structural integrity. It also carries many information about the sword itself, for example inscriptions from the swordsmith, such as signatures and dates, which offer insights into the sword's origin and the era it was crafted in. These markings are key for authenticating and appreciating the katana's historical and cultural significance.

Functionality of Nakago

To prevent breaking, Nakago is usually made of Shingane (心鉄 / 心金), which is soft and usually used as the inner part of the blade. Nakago is vital to a katana's use. It ensures the sword's structural integrity, keep the sword in good balance, and absorb the vibration from striking. Here are main functions of Nakago:

Structural Integrity: The nakago acts as the backbone of the katana, securely connecting the blade to the handle. This ensures the sword can withstand the impacts of cutting and striking without the blade becoming loose or detaching.

Balance: The shape, length, and weight of the nakago are designed to achieve optimal balance. This makes the katana easier to handle, allowing for swift and accurate strikes, which is very important in combat situations.

Vibration Absorption: When striking an object, the katana generates vibrations that travel down the blade. The nakago (and the tsuka together) helps absorb these vibrations, significantly reducing shock to the wielder's hand. This minimizes fatigue and discomfort, maintaining the user's control and precision during prolonged use.

Rat Tail Tang -- The worst type of tang you should avoid

We heard about the term "Full Tang Katana" a lot, technically speaking this is redundant word, because a real Katana should have long tang all the way inside the handle, and the tang width is close to the the blade.

But there are too many low quality "katana" in market don't have a functional tang. They are usually inexpensive ornamental stainless-steel katanas, feature a spot-welded tiny tang, which barely links the handle and blade together. This tang looks like a rat tail, hence get the name "rat tail tang" from the sword community.

We know from the traditional katana making process, that the tang and blade is one piece. But for low budget katana in modern days, the blade is usually cut out from steel plate, and to save cost, the manufactures will just spot welded a small metal stick as the tang, some are even as slender as chopstick.

Such swords are purely ornamental and should not be used for practice or cutting. Using these swords for practice and cutting can cause damage to yourself or others. Make sure you buy from reputable sword companies. And if you want to find out if your katana is full tang or rat tail, you can disassemble it. But at first glance, if you sword handle doesn't have Mekugi, it is likely a rat tail tang.

All romanceofmen katana are full tang and battle ready. No such thing as rat tail tang here. In our custom katana section you can see our full blade photos showing the tang as well.

Sword's Information from Nakago

Image source: Touken world

Nowadays, most budget katana features a functional nakago, that's good enough. But in ancient Japan, swordsmiths will leave many information on the nakago. In some senses, nakago is the canva for them, or as the nameplate for a katana.

Nakago is a crucial reference for appraising Japanese swords. sword from famous swordsmiths values a lot, naturally there are counterfeit katanas. Nakago has many information regarding the authenticity of katana, to help you identify real and fake katana. Here are the things nakago reveals:

-

Mei (銘) - Signature

- Identifies the swordsmith (刀匠) and their lineage.

- Indicates the historical era and potential geographical origin.

- Signifies authenticity and level of craftsmanship.

- Specifies the period or era (年代) when crafted, offering insights into the sword's historical and cultural context.

-

Yasurime (鑢目) - Filing Marks

- Reflects the unique style or school (流派) of the swordsmith.

- Shows craftsmanship quality and attention to detail.

- Provides clues to authenticity, based on consistency with recognized styles.

-

Mekugi-ana (目釘穴) - Peg Holes

- Indicates the sword’s history of use and ownership changes; multiple holes may point to re-handlings.

- The alignment and positioning offer insight into craftsmanship quality.

-

Rust (錆)

- Red Rust 赤錆: Suggests potential neglect or the sword's exposure to adverse conditions.

- Black Rust (Yokan-iro 羊羹色): Indicates well-maintained preservation, highly valued in antique swords.

- The uniformity and texture of the rust provide clues about storage conditions and maintenance history.

-

Shape and Condition of the Nakago (刀茎の形状と状態)

- Wear patterns may reveal the sword’s age and usage frequency.

- The overall condition hints at steel quality and forging techniques used.

-

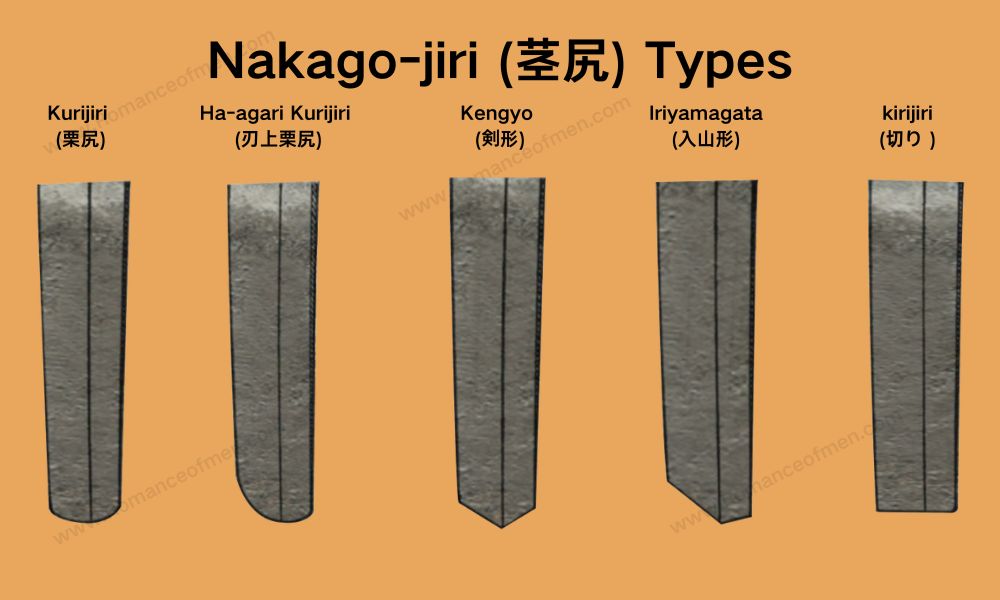

Nakago-jiri (茎尻) - End of the Tang

- The shape can indicate specific historical periods or swordsmith schools.

- Modifications or damage may hint at historical repairs or alterations.

Nakago Parts

The nakago (tang) of a Japanese sword is not just a simple piece of metal, it contains many features that contribute to the functionality or identity of a katana. Here's a list of parts on a nakago:

Nakago-jiri (茎尻): The end of the nakago, also known as (茎先 Nakagosaki) which varies in shape depending on the era and school. Common types include:

- Chestnut End (Kurijiri 栗尻): This is the most common type of nakago-jiri found throughout all periods of Japanese swords, characterized by its rounded end, resembling a chestnut.

- Blade-Rising Chestnut End (刃上栗尻 ): Similar to the Chestnut End with its roundness, but with a more pronounced angle on the blade side than on the spine side, starting from the ridge line (shinogi-suji).

- Sword Shape (Kengyo 剣形 ): This type has a symmetrically pointed tip, resembling the shape of a sword.

- Entering Mountain Shape (Iriyamagata 入山形 ): Unlike the Sword Shape, this style has a longer blade side and a shorter spine side, with a pointed tip.

- Straight Cut (切り ): This style appears as if it has been cut straight across, also known as "Ichimonji." Straight Cut nakago-jiri is often found on swords that have been shortened (suriage) and is rarely seen on swords in their original (ubu) condition..

Yasurime (鑢目): Filing marks on the nakago to prevent the blade from slipping out of the handle, it's also signal of the sword's age, school, or even the swordsmith's personal preferences, such as whether they were right or left-handed.

Early Yasurime was simple due to being left as hammered in the Jokoto (上古刀) era, but evolved into more decorative and functional forms in later periods, especially from the Shinto (新刀) period in early Edo era, with swordsmiths applying diverse designs for both slip-resistance and aesthetic enhancement. Common types of Yasurime include:

- Straight Filing (Kiri 切鑢): Horizontal marks across the tang.

- Right-Slanting Filing (Katte Agari 勝手上り鑢 ): The marks on the spine side slant slightly upwards, indicating a right-handed swordsmith.

- Left-Slanting Filing (Katte Sagari 勝手下り鑢 ): Opposite to Right-Slanting, where marks on the spine side slant downwards, often found on swords made by left-handed craftsmen.

- Diagonal Filing (Sujikai 筋違鑢 ): Marks slant significantly more than Right or Left-Slanting Filing.

- Large Diagonal Filing (Oosujikai 大筋違鑢 ): An extreme angle in the marks, typically over 45 degrees, seen in swords from specific regions and schools like the Chikuzen country (modern-day Fukuoka) Sukesada school and the Bitchū country (modern-day Okayama) Aoe school.

- Higaki Filing (檜垣鑢 ): Resembles a bamboo fence pattern.

- Hawk's Feather Filing (Takanoha 鷹の羽鑢 ): Marks form a pattern similar to a hawk's feather, slanting towards the blade.

- Reverse Hawk's Feather Filing (逆鷹の羽鑢 ): A pattern opposite to the Hawk's Feather.

- Decorative Filing (Kesho 化粧鑢 ): Designed not for practical grip but for aesthetic appeal, typically found on newer swords.

- Incense Bag Filing (香包鑢): A complex pattern inspired by the folds of a silk cloth used for wrapping incense, introduced by Tsuda Echizen no Kami Sukehiro from Settsu country (modern-day Osaka).

Mei (銘): The signature engraved on the nakago, including the swordsmith's name and the year the sword was made. Mandated by the Taiho Code (大宝律令) in the Nara period and became commonplace from the late Heian period. Engraving was typically done with a chisel (鏨 - たがね), but the Azuchi-Momoyama period saw the introduction of appraisal mei in gold inlay (金象嵌) for unsigned swords (無銘刀). Other than swordsmith's name and year, there are other signature types, we list the most common types here:

- Swordsmith's Signature (作者銘): The name of the sword's creator, reflecting the swordsmith's style and craftsmanship.

- Date Signature (年紀銘): Specifies when the sword was made, often found on the reverse side of the swordsmith's signature.

- Official Title Mei (受領銘): Honorary titles given to swordsmiths by authorities, indicating prestige.

- Ownership Mei (Shojimei 所持銘): Names the sword's owner, showing its historical lineage.

- Order Mei (注文銘): Denotes the individual who commissioned the sword, signifying custom craftsmanship.

- Red Lacquer Mei (Shumei 朱銘) and Gold Powder Mei (Kinfunmei 金粉銘): Use red lacquer or gold powder for inscriptions, avoiding tang damage.

- Test-Cutting Mei (試し銘): Documents the sword's performance in tameshigiri.

- Execution Mei (Saidanmei 截断銘): Details the use of the sword in executions, emphasizing the blade's sharpness.

Mekugi-ana (目釘穴): The hole(s) for the mekugi (peg) that secure the blade to the handle. The placement of these holes has evolved over time, moving closer to the center of the nakago in response to changes in sword design and usage. Multiple holes may exist due to re-handling or adjustments over the sword's lifetime.

Types of Nakago

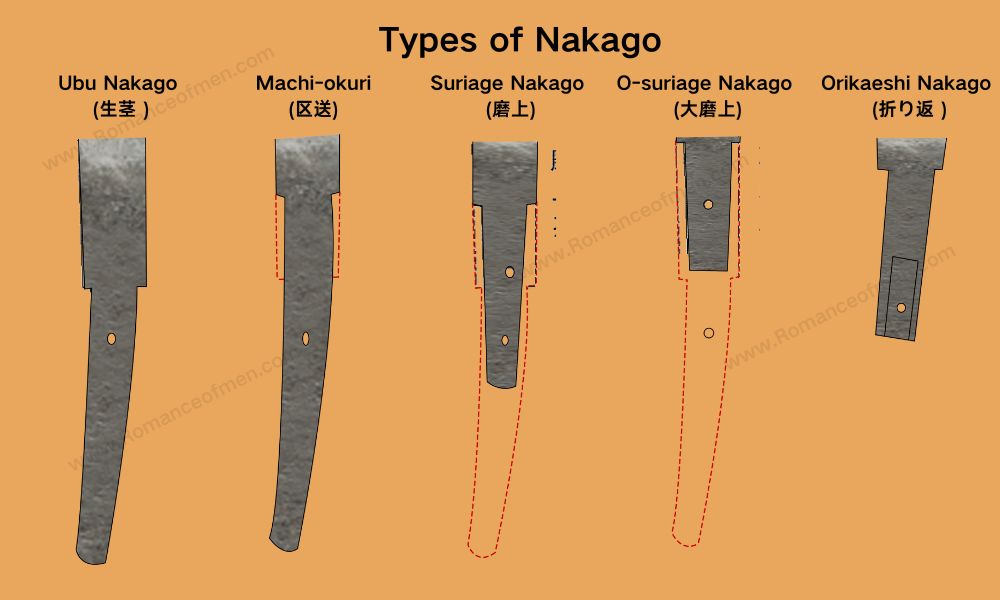

Many might not heard about this, but in ancient Japan, there is a common practice of shortening the nakago of Japanese swords, known as "suriage" 磨上. Because during the Nanboku-chō period, samurai often used long swords like "tachi" (太刀) and "ōtachi" (大太刀) from horseback. They are long and curved, designed for ease of use even when fully clad in samurai armor and mounted on horseback.

However, as battles shifted towards foot soldiers, the demand for shorter, more practical swords like "uchigatana (打刀)" increased. Uchigatana are worn with the blade facing up, making them easier to draw quickly. To adapt longer swords for this new style of combat, their tangs were shortened, a process also influenced by Edo period government regulations dictating sword length. This modification made the swords more compact and suitable for the evolving combat techniques.

Based on the level of modification, Nakago can be classified as the following. types:

Ubu Nakago (生茎 ): A tang that remains unchanged from its original state, not subjected to any shortening or reshaping. Its historical authenticity and lack of alterations over the years make it highly valuable and rare.

Machi-okuri (区送): This involves shortening the blade length by filing down the area above the "hamachi" (刃区 blade edge notch) and "munemachi" (棟区 back edge notch), effectively raising these notches without altering the tang itself. This process is also known as "Machi-age" (区上げ). While it modifies the blade, it doesn't change the tang, allowing the sword to still be considered ubu (unchanged).

Suriage Nakago (磨上): A tang that has been cut and shortened through the process of suriage, where the signature (mei) is preserved.

O-suriage Nakago (大磨上): A tang that has been significantly shortened during suriage to the extent that the original signature (mei) is cut out. Many Tachi from the Nanboku-chō period were shortened this way to make them more maneuverable.

Orikaeshi Nakago (折り返 ): A tang where the part with the signature is folded back to avoid losing it during excessive shortening, preventing the sword from becoming "O-suriage Mumei" (大磨上無銘), which means a greatly shortened tang without a signature.

Gaku-mei Nakago (額銘 ): A tang where the part bearing the signature is cut out and then embedded back into the tang. This method preserves the signature by relocating it rather than folding, ensuring the sword's historical and maker's marks are not lost during modification.

Nakago Shapes

There many shapes of the nakago in its original state (ubu), they are classified into seven types based on their length and form. The shape of nakago is a good indicator of the era, school, and swordsmith of the sword.

Standard Form (普通形): Seen throughout the Koto (古刀) to Shinto (新刀) periods, this is the most common shape.

Pheasant Thigh Form (Kijimomogata 雉子股形): Named for its resemblance to the thigh of a pheasant, this form was found from the Heian to the Kamakura period. It was typically used for "Efu Tachi" swords, carried by officials of the Imperial Guard Office (衛府 - Efu).

Swinging Sleeve Form (Furisodegata 振袖形): Common in tanto from the Kamakura period, this nakago features a pronounced curve from the base of the blade to the tip of the tang, reminiscent of the long, hanging sleeves of a traditional kimono.

Boat Bottom Form (Funagata 舟底形): Popular in the Sōshū tradition during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, named for its boat hull-like shape. Also known as "Sōden Nakago."

Bitterling Belly Form (Tanagoharagata タナゴ腹形): Seen in the works of Muramasa and his school during the Muromachi period, this shape bulges like the belly of a bitterling fish.

Grinding Stone Form (薬研形): Exclusive to the Hankei school in the early Edo period, this nakago resembles a grinding stone used for pulverizing medicine, featuring a gentle arc. Known as "Hankei Nakago" because it was solely produced by Noda Hankei.

Shinto Paper Offering Form (Goheigata 御幣形): Unique to Ise no Kami Kuniteru in the early Edo period, it is characterized by a notched bottom, resembling the paper offerings (Gohei) dedicated at Shinto shrines.