Ronin Explained: Japan’s Masterless Samurai and Their Struggles

Table of Content

What is Ronin?

A Ronin is a masterless Samurai, in Japanese the word "samurai" (侍) means "to serve," a ronin finds themselves without a lord to serve. They remain a bushi (武士, warrior), but their social standing and purpose are drastically altered. Beyond the privilege of carrying a sword and a surname, were no different from commoners.

The word "Ronin" (浪人) in Japanese originally referred to someone who left their registered land and wandered to other places, much like a vagrant. In ancient Japan, due to strict census systems, becoming a ronin could lead to many inconveniences.

However, the more commonly known meaning of ronin is a "masterless samurai." This became a recognized social status during the late Muromachi period. At that time, the term was written as "rōnin" (牢人). By the Edo period, the word changed to "rōnin" (浪人), though the pronunciation remained the same.

In modern Japanese, the word Ronin is still used to refer to those students failed college entrance exams, as well as for people who are unemployed and looking for jobs.

History of Ronin

A samurai could become a ronin for several reasons: their master might die, they could be dismissed, or they might choose to leave in search of better opportunities elsewhere.

During the Sengoku period, the relationship between samurai and their masters (daimyo) was more balanced. Japan was not unified, and ongoing wars created many opportunities for skilled samurai. If a samurai was dissatisfied with his master, it wasn’t uncommon for him to leave, become a ronin, and seek out a new master. In this turbulent era, ronin were like free agents. With so many daimyo fighting for power, some ronin even rose to become daimyo themselves. At this time, becoming a ronin was often a choice, allowing them to improve their status or find better careers.

However, after Toyotomi Hideyoshi unified Japan, the situation for ronin changed dramatically. Japan entered a long period of peace, and with no wars to fight, daimyo needed fewer samurai. Talented fighters were less important than a stable, loyal workforce. Becoming a ronin in this period meant losing income and status, which made life much harder.

In the Edo period, the number of daimyo decreased because the Tokugawa government abolished many of them. Many samurai were forced into becoming ronin, losing their privileges and incomes. Few samurai willingly chose this path, and those who did risked being blacklisted, making it even harder to find work with another daimyo. In peaceful times, being a ronin was less a matter of freedom and more like being unemployed in modern society. In fact, modern Japanese use the term "ronin" to refer to unemployed people or students who haven’t been accepted into college.

The Tokugawa government viewed ronin as a threat to their control. Many ronin had joined opposing forces in conflicts like the Siege of Osaka and the Shimabara Rebellion. To keep ronin in check, the government imposed many strict rules, including banishment and restrictions on residency, making it difficult for ronin to find new employment. They even prohibited ronin from traveling abroad.

The life of Ronin

During the Sengoku period, many ronin were originally farmers who joined wars because of poverty. After the wars ended, if they didn’t become official samurai, many of these individuals no longer wanted to return to farming. Instead, they used their combat skills in other ways, turning to criminal activities like robbery or becoming gangsters. These ronin often terrorized villages, traveling from place to place in search of money.

However, not all ronin followed this path. Some pursued honorable goals, such as perfecting their skills in swordsmanship. One famous example is Miyamoto Musashi, who became a legendary swordsman. Others, like Chikamatsu Monzaemon, left behind the life of a samurai and succeeded in fields like literature. Some ronin gave up their samurai status entirely and became successful businessmen.

In the Edo period, though ronin had lost their official samurai status, they were still allowed to keep their surnames and carry swords (daisho set, a katana and a Wakizashi), acknowledging their samurai heritage. However, their daily lives were often no different from commoners. They were governed by town magistrates, and many ronin lived in poverty, renting small homes and making a living through simple crafts—like making umbrellas. For those without special skills in areas like martial arts, scholarship, or medicine, life was particularly difficult. Some were even worse off than common people because they only knew how to fight and kill, leaving them unable to survive in a peaceful society.

In some cases, the wives of ronin had to work as prostitutes to support their families. These women were referred to as "Yotaka" (夜鷹), meaning "night hawks."

In the final years of the Edo period, ronin became actively involved in political movements. Many, like Sakamoto Ryoma from the Tosa Domain, left their restrictive domains to become ronin and pursued political and social reform. There were even instances where commoners or farmers illegally adopted samurai surnames and called themselves ronin. Groups like the Shinsengumi, who were often considered ronin, included many members from non-samurai backgrounds.

Ronin VS Samurai

Here are the main differences between a Ronin and a Samurai:

1. Status and Allegiance

Ronin: Originally a samurai, a ronin lost their lord due to the lord's death, banishment of the samurai, the destruction of the samurai's clan, or the samurai leaving the lord's service on their own. This left them without a master to serve.

Samurai: Belonged to a specific Daimyo (feudal lord) or the Shogunate, with a clear lord to serve and a defined place within the social hierarchy.

2. Social Standing and Economic Situation

Ronin: Upon losing their master, their stipend was revoked, often leading to poverty. They often had to make a living by teaching swordsmanship, working as bodyguards or mercenaries, and had a low social status.

Samurai: Received a regular stipend (usually in rice), enjoyed a high social status, and belonged to the shi (warrior) class.

3. Law and Rights

Ronin: During the Edo period, ronin might be banned from legally carrying the daisho (the paired swords symbolizing samurai status). In certain periods, they were even subjected to forced relocation or surveillance.

Samurai: Held the kirisute gomen privilege (the right to kill commoners who disrespected them) and were protected by the law.

4. Cultural Symbolism and Image

Ronin: In literature and drama, they are often portrayed as tragic heroes or rebels (like the Forty-Seven Ronin incident), or as symbols of freedom and wandering.

Samurai: Represented loyalty, honor, and discipline, and were the core symbol of Japanese feudal ethics.

5. Philosophy and Behavior

Ronin: Might turn to individualism after leaving the master-servant relationship, and some became scholars, artists, or wandering swordsmen (like Miyamoto Musashi).

Samurai: Strictly adhered to the "Bushido" spirit, emphasizing absolute loyalty to their lord and shini no kakugo ("preparedness for death").

6. Historical Outcome

Ronin: Some sought new lords, while others became farmers, merchants, or participated in rebellions (like the Shimabara Rebellion).

Samurai: After the Meiji Restoration, the samurai class was abolished, and most transitioned into bureaucrats, soldiers, or scholars.

FAQ about Ronin

Who is the most famous ronin?

There are many famous ronin in Japanese history, but the most renowned is undoubtedly Miyamoto Musashi. He is considered the greatest swordsman of Japan and became legendary for his undefeated record in sword duels. Musashi not only mastered the art of swordsmanship but also left a lasting legacy with his book The Book of Five Rings, which detailed his philosophy and strategies on combat and life. His journey as a ronin seeking mastery is one of the most celebrated stories in Japanese culture.

Is a ronin a ninja?

A ronin is not the same as a ninja. A ronin is a masterless samurai, while a ninja, also known as shinobi, was a covert agent or mercenary trained in espionage, sabotage, and assassination. That said, it’s possible that some ronin may have become ninjas if they needed to make a living. However, these two figures had very different roles in Japanese society, with samurai adhering to a code of honor (bushido), whereas ninjas operated in secret and were often seen as outcasts.

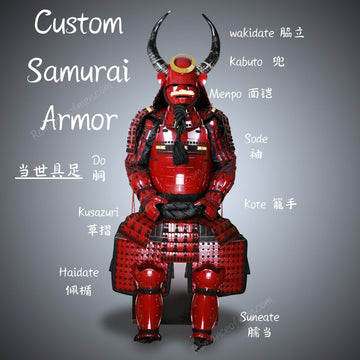

Did ronin wear armor?

It is unlikely that most ronin could afford a full set of traditional Japanese armor. Full suits of armor were typically expensive and for high-ranking samurai or daimyo. Lower-ranking samurai, like the ashigaru (foot soldiers), wore simpler and more affordable armor, such as hara-ate (a simple chest plate) or dōmaru (light armor). Since ronin often had limited resources, they may have only had access to light or piecemeal armor, if any at all. In times of peace, many ronin did not wear armor at all, as they were more likely to live like commoners.

Is it a shame to be a ronin?

The shame associated with being a ronin depends on the circumstances. In some cases, if a samurai’s master died and the samurai did not commit seppuku (ritual suicide) to follow their lord in death, this was seen as dishonorable. In other cases, a samurai who left his master voluntarily might not face as much shame, especially if he was seeking better opportunities. However, in the Edo period, being a ronin was often viewed as shameful because it meant a loss of income, status, and purpose. Without a master, ronin were often impoverished, and the prestige of being a "samurai" didn’t provide any real privilege or social advantage. Their low status and financial struggles made it difficult for them to maintain the honor traditionally associated with samurai.

Source Cited:

George Sansom : A History of Japan 1615-1867

Nitobe Inazo : Bushido: The Soul of Japan