Ashigaru : Everything you need to know about the Japanese Foot Soldiers

Table of Content

- What is Ashigaru?

- History of Ashigaru

- Ashigaru vs Samurai: Social Status

- Weapons of Ashigaru

- Armor of Ashigaru

- Necessary Supplies for Ashigaru

- Income of Ashigaru: Dangerous but Poorly Compensated

What is Ashigaru?

The term Ashigaru 足軽 in Japanese literally means "light feet," and it refers to foot soldiers hired by the samurai class. These soldiers were usually farmers who, during times of war, were recruited to fight for their landowners. Unlike the higher-ranking samurai, who wore full suits of samurai armor (even their horses were armored), Ashigaru usually wear limited protection armor such as Domaru, Haarate, often without Kabuto (helmets), only Jingasa, a simple conical hat.

A typical image of Ashigaru shows them wearing jingasa and haraate, wielding either a spear (yari) or a matchlock gun (tanegashima). These weapons were favored because they required less training compared to the swordsmanship and archery skills of the samurai.

History of Ashigaru

The origins of the Ashigaru can be traced back to the low-ranking servants known as kawaramono (下部) during the Heian period. These attendants were responsible for logistical and construction duties in times of war, as well as serving as backup combatants. Their role as support soldiers laid the foundation for what would later become the Ashigaru class.

As warfare in Japan evolved from individual duels to large-scale group battles during the Nanboku-cho period, the importance of Ashigaru grew. Many farmers were recruited as Ashigaru, functioning much like mercenaries. They were hired by daimyō, as well as temples and merchants seeking protection. However, in these early stages, Ashigaru were often disorganized, lacking loyalty and discipline. At times, they even formed unruly mobs, looting cities and causing chaos.

During the Sengoku period, daimyō began to organize and train Ashigaru more systematically. They were primarily taught to use yari (spears), yumi (bows), and matchlock guns (tanegashima), forming the backbone of large infantry units. These well-trained Ashigaru played a critical role in transforming warfare in Japan, significantly affecting the outcomes of battles and becoming an essential part of military strategy.

However, in the peaceful Edo period, the demand for Ashigaru decreased drastically. With no wars to fight, many Ashigaru were dismissed, returning to their former lives as farmers or becoming servants for the samurai class. Others became ronin—wandering, masterless Samurai.

Ashigaru vs Samurai: Social Status

In feudal Japan, a person’s social class—(samurai, farmer, craftsman, or merchant)—determined many aspects of their life, including salary, housing, employment, and even what clothes or weapons one could use.

Ashigaru were generally not considered full samurai, although their status varied depending on the region and time period. Originally, they were foot soldiers hired by the samurai class and ranked below the samurai, closer to commoners or peasants. However, in some regions, like the Kaga domain (加賀藩), Ashigaru were officially recognized as samurai, even just the the lowest rank, making the domain particularly attractive to Ashigaru.

During the Sengoku period, the social status of Ashigaru rose. Some Ashigaru commanders (足軽大将 Ashigaru taisho) were elevated to mid-level samurai status and earn a decent income. The most famous example is Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉), the son of a farmer who began his career as an Ashigaru and became a powerful daimyō , eventually unified Japan.

In the Edo period, Ashigaru often served in administrative or policing roles, but they were still considered lower-ranking retainers, not recognized as real samurai. Their status was marked by strict regulations on clothing and behavior, further distinguishing them from the samurai class. While a few Ashigaru were able to rise through the ranks or inherit official positions, most did not enjoy the same privileges as samurai, such as the right to carry a family name or the right to commit seppuku (ritual suicide).

Officially, the class status of an Ashigaru was not inheritable. However, in practice, many Ashigaru passed their positions down to their children. If an Ashigaru had no heirs, they could "sell" their status to a merchant or farmer, allowing others to become Ashigaru.

Weapons of Ashigaru

As frontline soldiers, Ashigaru mainly use bows, guns, and long-range weapons. Based on the type of weapons they used, Ashigaru were categorized into three main types:

1. Bow Ashigaru (Yumi Ashigaru 弓足軽)

Bow Ashigaru represented the oldest type of Ashigaru unit. During the battles of the Sengoku period, they were mainly used to fill gaps between the volleys of gun squads or when ammunition ran low. Yumi (Bows) had the advantage of being usable in any weather and could fire rapidly, making them effective for short-range combat. However, with the introduction of firearms, bows gradually lost their dominance. By the end of the Sengoku period, the number of guns on the battlefield had surpassed that of bows.

2. Gun Ashigaru (Teppo Ashigaru鉄砲足軽)

After the introduction of firearms in Japan, guns (Tanegashima) became the primary weapon on the battlefield. Though expensive and cumbersome—requiring time to reload, being less accurate initially, and unusable in heavy rain—their sheer firepower made them highly effective. The loud noise and thick black smoke from volleys also had a powerful psychological impact on the enemy. The leader of a gun ashigaru unit was known as the Teppōgashira (Head of the Guns).

3. Long-Range Weapon Ashigaru (Naginata Ashigaru 長柄足軽)

Long-range weapons in this context mainly refer to yari (spears), which became increasingly popular during the Muromachi period, eventually surpassing bows as the primary weapon for Ashigaru. Unlike guns, bows or swords, which required specialized training, spears were more accessible for untrained soldiers like Ashigaru. The yari, typically 4 to 5 meters long, allowed Ashigaru to keep their enemies at a distance, using simple thrusting techniques to pressure and corner opponents. The leaders of these units were known for their bravery and were called Naginata Taisho (Spear Generals) or Yari Bugyo (Spear Magistrates).

In addition to these primary weapons, Ashigaru also carried katanas. However, their katanas were often lent by their daimyō and were referred to as okashi gatana (お貸し刀), meaning "loaned katana." These mass-produced katana, also known as tabagatana (束刀), were of lower quality, often stamped with serial numbers on their scabbards, and were considered nearly disposable.

Flag-bearing Ashigaru (旗指足軽 - Hata Sashi Ashigaru)

Flag-bearing Ashigaru were tasked with carrying the banners (gunki 軍旗) of their daimyō or general. Though they were not direct combatants, this role was considered highly honorable. Because they were often prime targets for the enemy, brave and well-disciplined lower-ranking samurai (kashi 下士) were usually appointed to this position. It is said that three Ashigaru worked together as a unit to hold each flag, and the individual in charge of commanding these units was known as the Hata Bugyō (旗奉行, Flag Magistrate).

In addition to flag-bearers, some Ashigaru carried uma-jirushi (馬印), or horse standards, which served as symbols of the leadership on the battlefield. Those responsible for this duty were called Umajirushi-mochi (馬印持, Horse Standard Bearers).

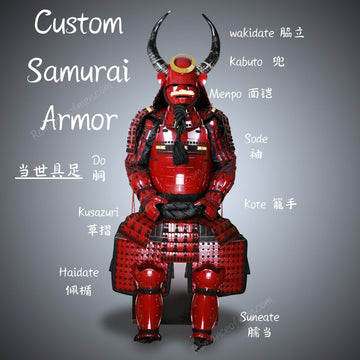

Armor of Ashigaru

Armor was expensive, and since most Ashigaru were farmers and often financially struggling, they could not afford to provide their own armor. Like their katana, Ashigaru's armor was usually loaned to them by their daimyō. This type of loaned armor was called Okashi Gusoku (御貸具足).

Okashi Gusoku was designed to be practical and one-size-fits-all, consisting of a breastplate (dō 胴), gauntlets (kote 籠手), and a simple conical helmet known as jingasa (陣笠), or occasionally a kabuto (兜). Both the jingasa and the breastplate often had crests (mon 紋) painted in red lacquer or gold leaf on the front and back, for identification on the battlefield.

Due to the physically demanding nature of their role, Ashigaru were expected to move quickly, performing various tasks on and off the battlefield. As a result, they typically did not wear thigh guards (haidate 佩楯) or shin guards (suneate 脛当). Instead, they wrapped their legs in cloth called habaki (脛巾) and wore straw sandals (zōri 草履) for speed and agility. Their gauntlets were also simplified, often lacking hand protectors (tekō 手甲) to allow for greater dexterity.

Necessary Supplies for Ashigaru

Ashigaru were equipped with essential supplies for three days during long marches and battles. A cloth was often draped from the back of their jingasa to provide shade from the sun or protection from the rain. For food, they carried hyōrō-dama (兵糧玉), which were dried rice balls (hoshii 干飯) made by steaming rice and then drying it into compact portions. These rice balls were wrapped in cloth, with each twist of the cloth separating a portion for a meal. The hyōrō-dama could be eaten as-is or softened in hot water, making it a practical preserved food.

In addition, Ashigaru carried bundles of braided yam stems or other plants that had been boiled in miso and dried. These ropes of preserved food could be cut into pieces and boiled in water to create instant miso soup. The jingasa helmet itself was sometimes used as a cooking pot for this purpose, allowing soldiers to prepare meals on the go.

Food supplies were typically provided after four days of marching, but access to clean drinking water was a challenge. Rivers were considered safer than wells, as wells were often contaminated by waste. The Ashigaru manual, Zōhyō Monogatari, gave practical survival advice, instructing soldiers to forage for edible plants, fruits, leaves, and even pine bark in enemy territory.

Rice was a staple of the Ashigaru diet, and each soldier was typically allotted around 1.8 liters of water per day, along with rice, small amounts of miso, and salt. Miso, valued for its high calorie content and ability to preserve well, was essential for flavoring foraged plants. It was carried in compact, dried forms, such as miso balls. Salt, provided in solid chunks rather than powdered form, was easier to transport and less prone to absorbing moisture.

Pickled plums (umeboshi) were another valuable food item, prized for their preservative qualities and medicinal uses, such as stopping bleeding and preventing fatigue. In times of water scarcity, soldiers were known to look at a plum to stimulate saliva. Dried vegetables like leeks, burdock root, and mushrooms were also carried as portable food items, originally developed as famine food, but crucial for long campaigns.

Income of Ashigaru: Dangerous but Poorly Compensated

Ashigaru were considered expendable and cheap resources in wartime. For example, when a retreat became inevitable, Ashigaru units were often assigned the role of Tonō (殿), which meant staying behind on the battlefield to cover the lord or general’s escape. Acting as decoys, these soldiers were essentially sacrificing their lives. The death rate for Tonō units was reportedly over 80%, making it a virtual death sentence. A gunken (military inspector) would supervise the Tonō unit, and anyone caught attempting to flee would be beheaded.

Even if an Ashigaru somehow survived the battle, their ordeal was far from over. After the fighting ended, those left behind faced other dangers, such as enemy soldiers or the so-called “loser samurai hunts,” where robbers targeted stragglers to steal armor and other valuables. These thieves would lie in wait to rob or kill injured soldiers. Survivors often had to hide deep in the mountains, staying constantly on alert to avoid being caught.

Despite risking their lives for their daimyō, Ashigaru did not receive a fixed salary. If they win the battle, Ashigaru were allowed to loot and plunder anything from the land. This practice of plundering was their unofficial reward. Victorious Ashigaru would ransack homes, steal valuables, and there are records of them even selling women and children left behind. Such acts were tolerated during times of war and were seen as part of the harsh realities of the battlefield.

*Image source of this article: From the book 雑兵物語