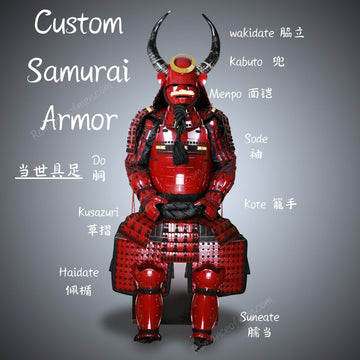

Samurai Armor Major Parts Explained

Samurai armor, a remarkable feat of military engineering, is a testimony of the ingenuity and skill of ancient Japanese craftsmen. This armor, worn by the samurai warriors of feudal Japan, was not only a protective gear in battle but also a status symbol, reflecting the strength and value of the wearer.

Understanding the parts of samurai armor is important for several reasons. Firstly, each component was meticulously designed with a specific purpose in mind, whether it was to protect a particular body part, allow for greater mobility, or to intimidate the enemy. Secondly, the armor parts and their arrangement can tell us a lot about the evolution of warfare tactics and technology during the Japanese feudal period. Lastly, the terminology associated with samurai armor provides a fascinating insight into the culture and values of the samurai class. Just as katana, there are many technical terms for samurai armor, in this article, we will dive into the world of samurai armor and help you better understand the most important parts, their history and developments.

Table of Content

Typically, a samurai armor set is composed of 3 parts designed to shield the head, torso, and limbs. The head was traditionally protected by a helmet, known as a kabuto, later supplemented by facial armor or mengu. The torso, specifically, was shielded by a type of breastplate called dō. The limbs, including the arms and legs, were protected by individual armor pieces collectively known as the sangu, or ‘set of three’. A standard sangu comprises a pair of armored sleeves, known as kote, which are identical but mirrored. The thighs were shielded by a single split apron-like panel named a haidate, while the shins were protected by a pair of shin guards, or suneate.

Most armor sets also included a pair of shoulder guards, or sode. Interestingly, while the sode are not technically part of the dō, they were usually crafted alongside the breastplate. There were times in Japanese armor history when warriors chose not to wear sode. Indeed, some armor types were even made without shoulder guards between the late 16th and early 17th centuries, a topic that will be elaborated on in subsequent chapters. However, for those just beginning to study Japanese armor, it’s advisable to assume that a full gusoku will always include a pair of sode.

Essential parts Introduction:

兜 Kabuto :

The “Kabuto,” is the helmet of samurai armor. Its design and structure have seen numerous transformations over time, mirroring the evolution of samurai armor.

Function:

The primary role of the Kabuto is to protect the skull and neck, areas of vital importance during combat.Additionally, it acts as a base for decorative elements, which can represent the wearer’s rank, reputation, or character.

Development and Progression:

The earliest Kabuto models were crafted in Tosa province, featuring a design that fit closely to the head. This design, referred to as the zunari kabuto or “head-shaped helmet,” was straightforward yet efficient, with a lengthy plate extending over the head’s crown.

The Kabuto’s design was influenced by earlier armors known as tanko, intended for ground combat with weapons like swords, spears, and bows. These initial Kabutos had a distinct beaked front for facial protection, leading to their contemporary Japanese name, shokaku tsuki kabuto or “battering-ram helmet.”

At the onset of a particular era, the helmet was a blend of the ancient shokaku-tsuki kabuto and mabizashi-tsuki kabuto. This hybrid laid the groundwork for all unique features of Japanese helmets.

The helmet was composed of 8-12 rectangular scales that formed the bowl (hachi). Each scale was vertically aligned and riveted to its adjacent scales with six large, domed rivets known as hoshi (“star”), earning the helmet its name—hoshi kabuto, or “star helmet.”

The Kabuto was also comes with decorations, with notable examples being the crescent used by Date Masamune, the antlers used by Honda Tadakatsu, and the sunburst used by Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

面頬 Menpo / Mengu:

The “Menpo,” also known as “Mengu,” “Men Yoroi,” or “Menoshitabō,” is a unique component of samurai armor. This war mask is frequently linked with the samurai warriors of Japan.

Function:

The Menpo acts as a face mask, offering facial protection during battle.

Development and Progression:

The Menpo was initially introduced as a partial face mask to adjust for the modifications in the shikoro neck guard, which progressively widened horizontally like a parasol to allow for easier head movement.

The inception of the Menpo came after the emergence of cheek protection in the late Heian period in a style known as “happuri,” which draped from the forehead over the cheeks. Another style, “hampo,” covered the jaw and cheeks.

Tracing the evolution of the Menpo is challenging due to its numerous changes over time. Nonetheless, it continues to be a significant and iconic element of samurai armor.

袖 Sode:

“Sode” is an essential component of samurai armor, acting as the shoulder guard.

Function:

The Sode operates as a shield, protecting the samurai’s shoulders and upper arms in battle. It can be shifted to cover the majority of the body by moving the shoulder forward, offering a clever solution for the samurai to manage his horse and wield a bow while maintaining a shield between his armor and enemy arrows. When the Sode is not required, it can be repositioned to the back by moving the shoulder in the reverse direction, granting the arms full mobility.

Development and Progression:

During the Late Heian and Late Kamakura period, the Sode was effectively utilized as a shield, both on foot and on horseback, although it was more efficient on horseback when using a bow.

The Sode experienced significant transformations over time. Initially, they were large and overstated in size, worn by generals and other high-ranking individuals. Those lower ranking samurais wore a more practical size of Sode, or a new variant called tosei sode. These were slightly curved, rectangular, and modestly sized.

Tosei sode were designed to hang from the fastenings of the kote, instead of hanging from the watagami, and had simple cord loops for this purpose fastened through holes in the top plate.

Another type of Sode, known as tsubo sode, had a jar-like appearance, narrowing towards the bottom. Another variant, hiro sode (wider shouder armor 広袖), had lames that gradually became flatter and wider towards the bottom. The ring that had been fitted inside the rear edge of the Heian period Sode to accommodate the rear cord was replaced on all Sode by an elaborate kogai kanamono, attached over the lacing on the fourth row of scales.

籠手 Kode:

The “Kote” is an integral component of samurai armor, functioning as the protection for the arms and hands.

Function:

The Kote is crafted to shield the samurai’s arms and hands during battle. It is especially effective in defending against strikes and arrows.

Development and Progression:

Up until the twelfth century, warriors only wear a single armored sleeve, specifically on their left arm. This was primarily to prevent the bulky armor robe sleeve from interfering with the bowstring rather than for protection. In the late 1100s, the practice of wearing matching sleeves on both the left and right arms began to emerge.

The earliest Kote did not include mail, but after the onset of the 13th century, it was commonly used to fill the spaces between the plates.

At the start of the 16th century, the old Kote were updated and new variants were introduced. The main objective was to enhance the protection of the arms and hands by incorporating more mail and steel plates.

胴 Do:

The “Do” is a key element of samurai armor, functioning as the chest guard.

Function:

The Do is crafted to shield the samurai’s chest during battle. It is especially effective in defending against strikes and arrows.

Development and Progression:

The Do was a significant component of the samurai armor, featuring a ring on the right breast for attaching items. A second ring was added to the left breast on some armors, which became virtually a standard during the Edo period.

The armorers subdivided and named the new types of Do based on minor differences in construction. A notable variant of this type of Do was developed in the Yukinoshita area of Kamakura, hence called a Yukinoshita Do (雪の下胴). Date Masamune invited Miochin Masaiye and his family to Sendai to craft armor in this style for both himself and his troops. During his stay in Sendai, Masaiye introduced changes and brought the style to its fully evolved form. Yukinoshita Do were composed of five sections which tapered towards the waist. The front and side sections were made of single plates while the back was typically constructed of vertical plates.

In Edo period, replicas of the old armors were being produced. Initially, these were pastiches incorporating features from different eras, but they gradually became more accurate, resulting in almost perfect copies of o yoroi, haramaki and domaru. Those with financial means went a step further and purchased old armors from temples, or searched family storehouses, and refurbished them for use. In a call for rationality, Sakakibara Kozan penned his book Chuko-katchu Seisakuben, urging samurai to abandon these revival armors and revert to using the more practical styles of the Momoyama period.

草摺 Kusazuri:

The “Kusazuri” is an important element of samurai armor, functioning as the protective gear for the hips and upper legs.

Function:

The Kusazuri is crafted to shield the samurai’s hips and upper legs during battle. It is especially effective in defending against strikes and arrows.

Development and Progression:

The term “Kusazuri” should not be equated with the hip armor made from lames. Numerous proto-historical instances of Kusazuri were constructed from suspended pieces of solid plate, similar to the tassets on some transition-period examples of pre-tosei makes of cuirass that were crafted in the Mōgami style.

While the majority of Kusazuri seem to have been made from horizontal lames, the number could range from as few as four to more than a dozen, depending on the width of each plate, other alternative forms of hip armor may have also been employed.

The bushi-haniwa, terracotta warrior statues, suggest that several seemingly different forms of Kusazuri were used. The bushi-haniwa are generally accepted as fairly accurate historical representations of the equipment that they were designed to depict, but it is quite possible that many of their portrayals contain errors.

Less than ten examples of iron-made Kusazuri have been discovered in conjunction with these cuirasses. However, this could be a result of organic materials, such as rawhide, or very thin metal plate having been used to construct the Kusazuri.

佩楯 Haidate:

“Haidate” is an essential element of samurai armor, functioning as the protective gear for the thighs.

Function:

The Haidate’s purpose is to protect the samurai’s thighs during battle. It is notably effective in defending against strikes.

Development and Progression:

Haidate didn’t really emerge in Japanese armor until around the thirteenth century. There were a few unique early styles that used hon kozane in an unconventional manner, but the haidate described here and for which I provide instructions are consistent with those of the sixteenth century.

Despite being portrayed in all the art and films, and every suit comes complete with a set, historians inform us that more often than not the samurai didn’t wear their haidate, considering them uncomfortable and likely to slow them down when on the run. However, having once been the victim of a sword called Thigh-bane, it is suggested that you create haidate and wear them when you fight. Your thighs will be grateful.

The majority of haidate were constructed with small metal plates that were either slightly rectangular, or thinner with a rounded top and bottom. The latter were called goishi gashira iyozane. A few haidate, such as those depicted above, left, were made to be worn almost as pants—consider them armoured short hakama.

臑当 Suneate:

“Suneate” is an essential component of samurai armor, functioning as the protective gear for the lower legs and knees.

Function:

The Suneate’s purpose is to safeguard the samurai’s lower legs and knees during battle. It is notably effective in defending against strikes.

Development and Progression:

The earliest suneate were three-plate greaves with no protection for the knee, which emerged around the twelfth century. These knee guards, like the suneate themselves, were constructed from steel or solidly lacquered leather. Later, they were made of brigandine. The body of the suneate originally was leg-fitting plates, but those of the sixteenth century were either fitted plates, a style called tsubo (“tube”) suneate, or splinted (shino suneate) like those used on the forearms of kote. Small sections of mail were often used to span the spaces between shino.

During the Nambokucho period, plate knee guards of considerable size were added to their upper edge to rectify the deficiency of not offering protection to the knees. Suneate fitted with these large knee guards are called Otateage suneate, fastened in place by simple ties of cloth or braid which fitted through metal loops riveted to the plates.

The world of samurai armor is vast and complex, with each piece having its own unique history and evolution. To truly appreciate the intricacies and nuances of these historical artifacts, You can check this guide that will help you understand deeper the terminology and details associated with them.