Tameshigiri, History, and Present

If you are unfamiliar with the art of Tameshigiri, it refers to the cutting tests against different objects with a Japanese Katana sword. The Tameshigiri has been in practice in Japan for a long time and is still widely practiced in the country and worldwide. Tameshigiri has a long and rich history, we will try to cover as much as possible about this centuries-old art form. So in the rest of this article, you can find all about its darkest history to the elegant and sophisticated practice it has grown into today.

Table of Content

- What does Tameshigiri mean?

- History of Tameshigiri

- Professional Tameshigiri cutter

- Way of Tameshigiri

- Sharpest katana in Tameshigiri

- Modern Tameshigiri

What does Tameshigiri mean?

“Tameshigiri” in Japanese is 試し斬り, means “Cutting Test.” Tameshigiri is not just a cutting test that evaluate the quality of a sword but also of one’s martial art. Additionally, it is also a common practice among sword collectors whenever they obtain a new piece of a katana sword.

History of Tameshigiri

Tameshigiri has a long history, with records dating back to the Azuchi-Momoyama period. As a weapon, the katana's sharpness was crucial. To evaluate that, Japanese used many objects, like bamboo, tatami mat , etc. However, the most infamous test involved human bodies.

Image source: 中村圭佑

From the Sengoku period to the early Edo period, Tameshigiri was widespread in Japan. Even daimyo (feudal lords) sometimes performed Tameshigiri themselves. The corpses of criminals were commonly used, with headless bodies pile up to test how many torsos a katana could cut through and how clean the cuts were. In some cases, living criminals were subjected to Tameshigiri as a form of execution.

There were even dedicated places and roles for this practice. For instance, the Aizu domain had a designated area called “tameshimonoba ためし者場" where anyone could perform Tameshigiri if they followed the rules. The Tokugawa shogunate appointed specialists called “Otameshiyaku 刀剣御試役" (official sword testers), with Yamada Asaemon Sadaaki being the most famous one.

During the early Edo period, Tameshigiri was so popular, At one point, it even became an event people would gather around to watch Tameshigiri being performed. That lead to a shortage of dead bodies. To secure the supply, people would request priority for corpses from execution grounds or bring back unidentified bodies that found on riverbanks. Over time, people began to fear becoming criminals, being executed, and then having their bodies used for Tameshigiri.

However, as time passed, the brutal nature of Tameshigiri led to a decline in interest. In 1870, the practice of Tameshigiri on executed corpses was prohibited. Today,Tameshigiri is solely a martial art activity.

Professional Tameshigiri cutter

Under the Tokugawa shogunate, there were official sword testers known as "刀剣御試役" (Otameshiyaku). The most renowned among them was Yamano Kaemon (山野嘉右衛門), who is said to have tested over 6,000 bodies. His extensive experience earned him the authority to advise swordsmiths. In recognition of the souls he had tested upon, he even rebuilt a temple in their honor.

Yamano Kaemon's skills were passed down to his disciple, Yamada Asaemon Sadatake, and the Yamada Asaemon family continued to serve as official sword testers for generations.

As possibly the most frequent practitioners of Tameshigiri, their experience also made them experts in sword appraisal. The fifth generation of this family created a sword ranking book called "懐宝剣尺" (Kaihou Kenjaku), where Japanese swords were classified based on their cutting performance, there are 4 rankings: "Saijo O-Wazamono" (最上大業物), "O-Wazamono" (大業物), "Yoki-Wazamono" (良業物), and "Wazamono" (業物).

However, being an official sword tester was not a highly paid profession. To increase their income, they engaged in side businesses, such as selling corpses to others interested in performing Tameshigiri. Another side business, which might sound horrify today, involved the sale of medicines made from the livers of the corpses. In ancient Japan, it was believed that human liver had health benefits, especially when sourced from the bodies of men (since the corpses of monks, women, commoners, or those with disabilities were not used for Tameshigiri).

The eighth and final generation of Yamada Kaemon retired in 1882 (Meiji 15), marking the end of this unusual profession.

Way of Tameshigiri

Image source: Wikipedia

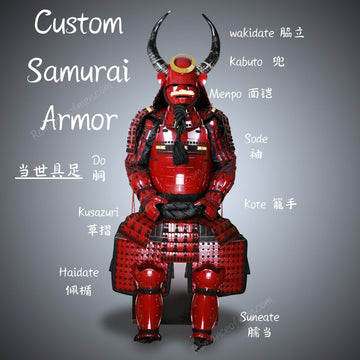

Tameshigiri required exceptional skill to be performed effectively. When Tameshigiri was conduct on living person, it’s called 生き試し (iki-tameshi). When on dead bodies, it’s called 据物斬り suemonogiri or 死人試し shibito-tameshi. When on hard objects, it’s called 堅物試し katamono-tameshi. Hard objects included iron plates, sword guards (tsuba), deer antlers, or helmets (kabuto) from the Japanese armor.

In any form of Tameshigiri, only those with exceptional skill could successfully cut the target; otherwise, the sword could become damaged or, in the worst cases, even break. Another factor is the weight of the sword, It was believed that the heavier a sword was, the better it could cut. To increase the weight and reinforce the katana blade for Tameshigiri, an iron pipe was used for tsuka (handle) instead of traditional koshirae. This pipe was called "切り柄" (kiritsuka).

A similar design was used for Tanto, but instead of a pipe, a heavy lead tsuba (guard) called "試し鍔" (tameshi-tsuba) was used.

When performing Tameshigiri on dead bodies, a special platform called "dodan" (土壇) was prepared by mixing sand and soil. Four bamboo stakes were erected at the four corners of the dodan, and the corpse was secured between these stakes, with the right side placed on top, the left side on the bottom, and the back facing the person performing the cut.

There are different names for cuts on different parts of the dead bodies, they are:

太々 (Futobuto): Near the clavicle.

雁金 (Karigane): The area where armpit hair grows.

乳割り (Chiwari) :In the early Edo period, it referred to the area slightly above the nipples where the ribs are prominent. In the late Edo period, it referred to the area around the solar plexus, which is easier to cut.

脇毛 (Wakige) : Slightly below 一の胴 (Ichinodō), around the upper part of the 8th rib.

摺付け (Suritsuke): Slightly below 二の胴 (Ninodō).

一の胴 (Ichinodō): Slightly below 三の胴 (Sannodō).

二の胴 (Ninodō): Slightly below 本胴 (Hondō).

三の胴 (Sannodō) : Slightly below the 8th rib area.

車先 (Kurumazaki): Slightly above the navel.

両車 (Ryōguruma): Slightly below the navel.

The number of corpses a sword could cut through determined its evaluation. Classifications included "Hitotsudō-kirioroshi" (cutting through one torso), "Futatsudō-kirioroshi" (cutting through two torsos), and so on, with "Nanatsudō-kirioroshi" (cutting through seven torsos) being the highest achievement.

生き試し Iki-tameshi

Iki-tameshi, or the living human cutting test, was usually conducted on criminals sentenced to death. However, during the early Edo period, there was a brutal practice where a samurai could attack and cut down people on the street to test their skills. This practice was known as "辻斬" (Tsujigiri). Fortunately, this horrific act was eventually forbidden in the late Edo period.

堅物試し Katamono-tameshi

"Katamono-tameshi" involved cutting through hard objects such as armor, iron plates, or helmets (Kabuto). This test focused more on the sword's durability—whether the blade would bend or break—rather than its sharpness.

截断銘 Setsudanmei

After a sword was tested, the results were recorded on the tang (Nakago) of the katana. This type of inscription is called "截断銘" (Setsudanmei). The Setsudanmei detailed the cutting test, including information such as "when" the test was performed, "by whom," "which part" of the body was cut, and "how many parts" were severed during a tameshigiri test using a prisoner's torso.

Because testing on human bodies was only permitted by the official sword testers ("刀剣御試役"), the cost of inviting them to evaluate a sword's sharpness was quite high. The service included not only the preparation for the test (labor costs, securing bodies, etc.) but also the engraving fee, which often used the gold inlay method. As a result, swords with 截断銘 (Setsudanmei) inscriptions are usually more expensive.

Sharpest katana in Tameshigiri

The katana with the most impressive and reliable record in test cutting is the "Nanatsudō-otoshi Kanefusa" (七つ胴落とし兼房). While many swords have records of cutting through 3 or 4 bodies, which is considered extremely sharp, cutting through 7 bodies in a single strike is extraordinary.

According to historical records, this remarkable feat occurred in 1681. The swordsman, Nakanishi Jūrobei Nyūkō (中西十郎兵衛如光), performed the cut. He climbed up a ladder and then jumped off to strike down, much like scenes depicted in anime. Because 7 bodies stacked together are taller than an average person, he needed to execute this legendary cut from an elevated position.

Modern Tameshigiri

In modern times, tameshigiri is practiced in martial arts such as iaido and battodo. The target for tameshigiri is no longer a human body but rolled tatami mats. These mats, typically half or full tatami, are rolled tightly, tied with string or secured with rubber bands, soaked in water for a few days, and then placed on a cutting stand. The practitioner then performs cutting strikes on this target, which is how tameshigiri is conducted in modern martial arts.

There are also rules in modern tameshigiri competitions designed to minimize the influence of a good sword and focus more on the swordsman's skill. Below are some basic rules to help you understand how it works:

Rules about the swords

The sword should weigh no more than 1100 grams (without the saya).

Only Shinogi-zukuri blades are allowed; Hira-zukuri blades are not permitted. This is likely because Hira-zukuri blades are sharper and make it easier to cut soft targets, such as tatami mats.

Each player is required to roll their own tatami mat. Players have two chances (using two tatami rolls). The competition begins when the player enters the area, and they are not allowed to test the distance or practice the cut beforehand.

As soon as they enter the area, the player must cut using the technique they have previously claimed, continuing until they either succeed or fail. The cut must end with chiburi (血振, the move to shake the blood off the blade). Higher points are awarded for more difficult moves, simulating the experience of an actual battle.