Kamon: Complete guide to understand the Japanese family crest

Table of Content

What is Kamon

Origin of Kamon

Who can use Kamon

Where to use Kamon

Common Types of Kamon

The Top 10 kamon

What is Kamon

If you like Japanese culture, you’ve probably noticed that there are many “logos” on Japanese items — whether on their flags, katanas, or samurai armors — you often find these fascinating-looking symbols. These “logos” are called Mon. They’re not just beautiful; they also hold deep meaning in Japanese culture. In this article, we’ll tell you more about them.

Mon (紋) literally means “pattern” in Japanese. Kamon (家紋) means “family pattern,” which you can understand as the identity of a family. You can think of Kamon as a “visualized family name,” because in ancient Japan, only nobles had family names and could read. With Kamon, even illiterate commoners could recognize which family a person belonged to.

Origin of Kamon

The history of Kamon can be traced back to the Jōmon period. The patterns and shapes found on Jōmon and Yayoi pottery are extremely diverse, and archaeologists believe that each design carried its own meaning. Over time, these patterns evolved into what we now know as Kamon.

There are two major theories about the official origin of Kamon in Japanese history. The most widely accepted one is the Gissha (bullock cart / 牛車) theory. During the Heian period, nobles often traveled in bullock carts for social activities. At that time, most carts were simply painted black. To display their authority and elegance, nobles began decorating their carts with unique patterns and emblems — which eventually became their family crests.

Another theory suggests that Kamon developed from the decorative patterns on nobles’ clothing. Some families particularly favored certain designs and later adopted them as their family emblems.

In early Japan, there were four major noble families — the Genji (Minamoto), Heishi (Taira), Fujiwara, and Tachibana — collectively known as the Genpei Tōkitsu (源平藤橘). Some branches of these families moved to other regions and created their own unique Kamon. Over the centuries, the number of Kamon in Japan grew tremendously. According to the book 日本的家纹大全 by Honda Sōichirō, there are about 5,000 recorded Kamon, while unofficial records suggest there may be more than 20,000 across Japan.

Who can use Kamon

In the beginning, only nobles were allowed to use Kamon. Later, the samurai class also began using them—especially on the battlefield—where Kamon appeared on flags to help identify allies and enemies.

As time went on, particularly during the Edo period, common people also began using Kamon widely. Merchants, craftsmen, and even farmers adopted them as family symbols, often choosing designs that carried auspicious or blessing meanings.

Some business families have lasted for many generations, and in modern times, many of them continue to use their Kamon as company logos. A famous example is the Mitsubishi logo, which combines elements from two traditional family crests — those of the Yamauchi and Iwasaki families.

Where to use Kamon

Kamon were most commonly used on battlefields to distinguish allies from enemies. You can often see Kamon displayed on battle flags (旗指物 / sashimono) — for example, the Takeda clan’s “Takeda-bishi” banner, which served as a rallying signal for troops during the Battle of Nagashino.

They also appeared on camp curtains (陣幕 / jinmaku), such as the Ashikaga clan’s “Nihikiryo-mon” design, used to mark the position of the main camp. In the historical chronicle Taiheiki, the term “Nihikiryo” was even used to directly refer to the Ashikaga army itself.

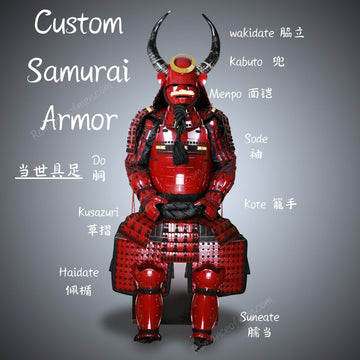

Kamon were also engraved or embroidered on armor and weapons, such as on helmet crests (maedate) or sword scabbards. For example, Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s battle surcoat (jinbaori) was embroidered with both the Paulownia (Goshichi no Kiri) and Mokko crests.

The Emperor sometimes granted specific Kamon to loyal retainers as a symbol of honor. For instance, Emperor Go-Daigo awarded Ashikaga Takauji the Goshichi no Kiri crest, and Oda Nobunaga received the Kiri and Hikiryo crests for supporting Ashikaga Yoshiaki. These imperial crests, known as Gomon (御紋), were often used on official documents and ceremonial items, representing imperial recognition and authority.

Kamon are also commonly used in traditional Kimono, where their placement follows strict conventions. For example, formal mourning attire typically features five crests — one on the back, one on each sleeve, and two on the chest — which represents the highest level of formality. Wedding kimono usually have three crests — one on the back and one on each sleeve — while everyday garments for commoners often bear a single crest.

Kamon are also widely used on everyday objects, such as lacquerware (bowls and trays), cutlery, folding fans, and even on a samurai’s sword cord tassel (sageo). They also appear in architectural decorations, including door lintels, folding screens, and wooden pillars. For instance, the ceiling of Nijō Castle in Kyoto still displays the Tokugawa clan’s triple hollyhock crest (Mitsuba Aoi).

Kamon are even used on tombs and gravestones. In modern Japan, families can still trace their lineage through the Kamon engraved on ancestral graves. Surveys have identified nearly 20,000 different Kamon appearing on tombstones across the country.

Common Types of Kamon

Based on their design themes, Kamon can generally be divided into five categories: Animals, Plants, Nature, Architecture and Transportation, and Objects & Patterns.

Animal Kamon include creatures like turtles and cranes, which are associated with longevity and carry the wish for the family’s enduring prosperity.

Plant Kamon include symbols of wealth and status, such as wisteria and peonies, which also represent elegance. The Tokugawa clan’s hollyhock crest (Aoi-mon) belongs to this category as well.

Architecture and Transportation Kamon include designs like carts (sha-mon), often based on bullock carts, symbolizing the luxury of the nobility. Torii gate patterns indicate a family’s priestly or sacred lineage.

Nature Kamon feature elements such as the moon, mountains, and lightning, expressing reverence for nature and prayers for abundant harvests.

Objects & Patterns Kamon include designs derived from tools or abstract motifs. For example, a clamp (batsugiki) represents construction-related professions, while parallel horizontal lines known as Hikiryo (引両) are said to have originated as a stylized dragon motif.

Kamon can also be classified based on their usage. The official family crest (定紋 / Teimon) is formally used by a family, while alternate crests (替紋 / Kaemon) are created by individuals for informal occasions. After marriage, women sometimes design a personalized crest (女紋 / Onna-mon) by incorporating part of their natal family’s Kamon.

There are also general crests (通紋 / Tsū-mon), which do not belong to any particular family or individual and can be used by common people mainly for decorative purposes. Temple crests (神紋 / Jin-mon or 寺紋 / Ji-mon) are used exclusively by temples.

One of the most interesting types is the Hiyoku-mon (比翼紋 / ひよくもん), a type of family crest created by placing two different crests side by side, symbolizing a man and a woman who are deeply in love.

The Top 10 kamon

The Ten Great Family Crests (Jūdai Kamon) refer to ten of the most widely used Kamon (家紋 / family crests) in Japan. These are:

Kashiwa-mon (柏紋 / Oak Leaf Crest)

Kashiwa (Oak) is a tree in the beech family, and its leaves are traditionally used to wrap kashiwa-mochi, a sweet eaten during Tango no Sekku (Boys’ Festival). These thick leaves were historically used as plates for offering food at Shinto shrines. Because the oak tree was considered sacred, the Kashiwa-mon was often adopted as a family crest by priestly households.

Katabami-mon (片喰紋 / Wood Sorrel Crest)

Katabami (Wood Sorrel) is a perennial plant that grows abundantly along roadsides and in shaded areas. Because of its strong ability to propagate, it has been used in family crests to symbolize the wish for prosperous descendants.

The design, with three leaves arranged in balanced symmetry, resembles the Aoi-mon. As a result, when the Edo Shogunate prohibited families other than the Tokugawa from using the Aoi-mon, many samurai households switched to the Katabami-mon instead.

Kiri-mon (桐紋 / Paulownia Crest)

Historically used by the imperial family and other high-ranking households, the Kiri-mon later became a symbol for many public institutions, including the Japanese government. Unlike other crests used by elite families — such as the Tokugawa clan’s Aoi-mon or the modern Imperial Chrysanthemum Crest — which were often restricted by law, the Kiri-mon was allowed for widespread use. A famous historical example is the Toyotomi clan, now extinct.

Taka no Ha-mon (鷹の羽紋 / Hawk Feather Crest)

Hawk (Taka) is a swift, brave, and elegant bird, and its feathers were even used to make arrow fletchings. Because of these qualities, the Hawk Feather Crest (Taka no Ha-mon) became popular among samurai families.

There are many variations of this crest. For example, the Chigai Taka no Ha features crossed feathers, while the Narabi Taka no Ha places two feathers side by side. In total, more than 60 distinct Hawk Feather crests have been documented.

Tachibana-mon (橘紋 / Tachibana Orange Crest)

Tachibana (橘 / Tachibana Orange) is an evergreen tree in the citrus family. A famous example is the Ukon Tachibana, planted in the front garden of the Shishinden at the Kyoto Imperial Palace.

The Tachibana-mon, a stylized design of its flowers, was favored not only by the Tachibana clan, a noble family, but also by samurai households, who appreciated its association with the “Tachibana flower” (Tachibana no Hana).

Tsuta-mon (蔦紋 / Ivy Crest)

Tsuta (Ivy) patterns have been a popular motif since the Heian period, appearing in emakimono (painted handscrolls) and on decorative furnishings. Because of its vigorous growth, ivy came to symbolize prosperous descendants, making it a favored choice for family crests.

The 8th Tokugawa shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune, was also fond of the Tsuta-mon and is known to have used it as a Kaemon (alternate crest), separate from his official family crest.

Fuji-mon (藤紋 / Wisteria Crest)

Fuji (Wisteria) is the family crest of the Fujiwara clan, a noble family descended from Nakatomi no Kamatari, later known as Fujiwara no Kamatari, who played a key role in the Taika Reform during the Asuka period.

The Fujiwara clan produced many high-ranking officials in the imperial court over successive generations and extended their influence nationwide as regional governors. Branches of the Fujiwara family, as well as prestigious offshoots such as the Kujō, Nijō, and Ichijō families, also used the Fuji-mon (Wisteria Crest).

Myōga-mon (茗荷紋 / Japanese Ginger Crest)

Myōga (Japanese Ginger) is a plant in the ginger family, also used as a culinary herb. Its name is associated with “divine protection” (冥加 / myōga), which made it a popular crest among samurai, who risked their lives in battle.

It was also believed to be a miraculous remedy that could dispel worldly desires, which is why it became a motif for temples and shrines as well.

Mokko-mon (木瓜紋 / Gourd-Shaped Crest)

Common among samurai families and those in woodworking-related professions, It is called Mokko because the shape resembles the cross-section of a gourd (kyūri). this crest was famously used by Oda Nobunaga and the Oda clan.

Omodaka-mon (沢瀉紋 / Arrowhead Plant Crest)

Omodaka (Arrowhead Plant) is a perennial plant that grows naturally near water. The character “瀉” in its name means “flowing water.” Its leaves are said to resemble a human face, which is why it was called Omodaka.

Because the pointed leaves resemble spears or arrows, it was also nicknamed the “Victory Plant”, making it a popular choice for samurai family crests.